Farmers’ suicide rates, mental health draw conversations

Programs aim to assist farmers; new programs are in the works

October 27, 2019

Studies show that farmers’ suicide rates have been nearly four times higher than that of the general occupational population, but calculating those rates is extremely difficult and unique to the agricultural profession.

While it is a challenge to study farmers’ suicide rates, it is critical in also determining ways to promote suicide prevention.

Additionally, after decades of mental illness, stigmatization and suicide, farmers and agricultural workers are becoming more comfortable expressing their struggles and seeking professional help, says a rural safety program coordinator.

Many assistance programs available today educate those who work with farmers on how they can help, but new programs are currently being developed to target farmers specifically.

Farmers and suicide rates

Amy Rademaker, rural health and farm safety program coordinator at Urbana-based Carle Hospital, said suicide rates for farmers are higher than that of the general rate for all people with occupations.

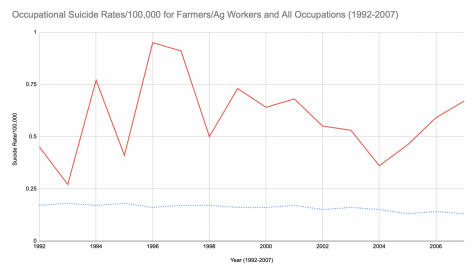

According to a 2014 study from the University of Iowa, the average general occupational suicide rate/100,000 from 1992 to 2007 was 0.16. The average occupational suicide rate/100,000 for farmers and agricultural workers for these years was 0.59.

The CDC’s numbers and the confusion surrounding them

Josie Rudolphi, an agriculture safety and health professor at the University of Illinois who is researching the data sets, said talk of suicide rates for farmers grew in popularity after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a study that showed farming was one of the deadliest occupations in 2012 and 2015.

“The CDC released a report in late 2016/2017 that farmers have the highest rate of suicide of all occupations, and that got people real interested, and (they) started to look more critically at the issue and I think the bigger issue: farmers’ mental health,” Rudolphi said. “But then, suddenly the CDC retracted the article, saying that they admit there were flaws in the classification of some workers and definitely some limitations to that data set.”

The CDC replaced the original study with another, published on Nov. 15, 2018, which turned some heads and confused a lot of people.

Rudolphi said the confusion stemmed from the limitations and classifications of the study.

For example, one of the limitations of the study was that data was taken from only 17 states in the U.S., not including Illinois.

Additionally, the farmers people might typically imagine (owner-operators) did not have their own category. Instead, these workers were placed in the management category.

“(The owner-operator of a farm): Those are hired workers. Owner-operators are considered managers, and they rank probably ninth in terms of rate of suicide by occupation,” Rudolphi said. “However, when we talk about managers, we’re talking about farmers, but we’re also talking about high school principals and CEOs and CFOs, so really it’s a mixed bag of ‘managers,’” she said.

There actually is a farming, fishing and forestry category (some people refer to it as Triple-F), but owner-operators do not go in that category.

Rudolphi said she thinks the numbers for owner-operators would be too small to place in its own category, which could be why this demographic of ag workers was placed in “managers” instead of “farming, fishing and forestry.”

“I think we just don’t have the numbers there,” she said. “The farming population is less than 2 percent of the entire population, and so if we broke farmers and had that owner-operator as their very own category, it would be incredibly small. And then when you have really small numbers, you are limited in what you can do statistically.”

Why it is difficult to calculate farmers’ suicide rates

Red: Farming/Ag worker suicide rate

Blue: Other occupations rate.

Numbers courtesy of the University of Iowa.

Rademaker said calculating the suicide rate of farmers is difficult because of the nature of ag-related professions: Farming is one of the most

dangerous professions in the U.S.

Rudolphi said the occupational fatality rate in agriculture is about 8 times higher than all other industries.

“All other industry rates is about 3.4 per 100,000 and agriculture is about 22.8 per 100,000,” she said.

Rademaker said what may appear as an agricultural occupational fatality might actually be a suicide. For example, falling into a grain bin and suffocating could be either a suicide or an accidental death.

“Not only is the data hard to interpret because of the variety of people that make up the demographic, it’s also hard because unless it’s a clear-cut ‘no,’ as with any suicide, farmers just have a lot more lethal means than the general population to for sure know the cause of death,” Rademaker said.

Even the most gruesome ways to die on the job could be the result of suicide, like getting run over by a tractor, she said.

“You can (intentionally) fall off and run over yourself,” Rademaker said. “You can start a tractor from the ground and get killed. We see that, too.”

Rudolphi said some people might infer that the U.S. is underreporting farmers’ suicide rates because they are being disguised as accidents.

However, if researchers were to use that logic, they would need to apply it to all other accidents as well in their analyses, she said.

“So we suggest that perhaps we’re underreporting the number of suicides, but I think that if we’re going to use that sort of reasoning, we’d have to apply that to the non-agricultural world as well,” Rudolphi said. “So you have to think: How many car crashes are suicides disguised as traffic crashes? … I’m more careful in suggesting that we’re grossly underreporting suicides because they’re being disguised as accidents.”

How farmers’ struggles are unique to the profession

Rademaker, whose family has been farming a little over 100 years, said farms are farmers’ livelihoods, not just their jobs. Many times farms are also passed down through multiple generations. So it is not just a livelihood, it is also a family legacy.

These factors put added pressure onto farmers to stick through with the profession and succeed despite adversity, she said.

Farmers are also isolated or separated from other people for long hours of the day every day, Rademaker said. A farmer may go 12 or more hours a day with little or no contact with anyone else.

The biggest factor boils down to the mentality of farmers, Rademaker said.

“Their mentality has always been, ‘We figure it out, we work through things, good or bad,’ and often times farmers also operate with a lot of isolation,” she said. “They’re kind of raised to be stoic, and it’s how they’ve been raised. I think a lot of it has to do with they feel like if they have to get out of the business (and) they have to sell the farm for financial reasons, they have failed both ends: They have failed their parents, their grandparents and their great grandparents, and they’re failing their children and their grandchildren. So that’s a tough burden.”

Another issue farmers face is something Rademaker said she believes people do not talk about enough: succession planning.

Succession planning focuses on figuring out what will happen to farming operations after the owners and operators have died. She said many farmers do not even plan for it.

“After you’re dead and gone, what does that farming operation look like? Who gets what, who’s responsible for what and what is the financial implications for what they’re about to inherit?” Rademaker prosed. “Most farmers will tell you, ‘My parents didn’t tell me, I’m not telling my kids; they’ll deal with it after I’m gone.’”

Rademaker said if farmers are not already planning for who gets what after they die, they will sometimes wait until the last possible minute to plan.

Sometimes farmers, like Rademaker’s own father, will wait until they are running out of time to make plans because of illness. Instead of postponing these plans until there is no time left, or not planning at all, Rademaker said farmers need to think about these things now.

There are also things farmers have no control over, like the economical factors, she said. Farmers are not seeing the return on their investments for certain crops, which is totally out of their control, Rademaker said.

“Right now, a bushel of wheat at our local elevator, you can get paid $4.74. The cost to produce that bushel of wheat, with all your inputs, is $3.57,” Rademaker said. “That means your rate of return is $1.17 for every bushel you harvested. That bushel will produce 70 loaves of bread, yet a farmer might spend over $1.17 to buy one of those loaves. That’s how messed up the pricing is.”

In terms of farmers’ mental health, Rudolphi said she screened young farmers and ranchers in four upper Midwestern states, not yet including Illinois, for anxiety and depression in one of her first surveys. Rudolphi and her colleagues did not diagnose anyone surveyed.

However, she said she found that almost 70 percent of the young farmers and ranchers met criteria for at least mild symptoms of anxiety. About 60 percent reported symptoms of at least mild symptoms of depression.

“Those are very high; that’s higher than what we see in the general population,” Rudolphi said. “For anxiety and depression in the general population, they say it’s about 1 in 5, so about 20 percent.”

Charleston farmer Alan Metzger said there are some other external forces farmers have no control over.

For example, the weather is instrumental in determining what crops can be planted when. Over the summer of 2019, parts of Illinois, including Coles County, saw incredibly wet weather, which resulted in many parts of farmers’ fields to flood before planting, Metzger said. This delayed planting to an extreme degree, which added stress to many farmers, including himself.

“Historically, I know that anything planted after day 15 is going to reduce my yield,” Metzger said. “They’re forecasting rain every few days (during planting season), and even when they don’t forecast rain, we were getting rain. It’s just very, very stressful.”

Tonya Eich, manager for the Coles County Farm Bureau, said farmers all over the state were experiencing the mental strain that came with predictably wet, then surprisingly dry weather. It delayed the planting of many farms so much that some crops could not get planted at all. Eich said the closer to rivers farms were, the worse it was.

Many farmers not just in Illinois, but also in the Midwest, found themselves in bleak financial situations, she said. Many of them went thousands of dollars into debt or took out insurance payments as a last resort, Eich said.

When farmers find themselves in financial crises, sometimes they believe suicide is the only way out, she said.

Keeping the mental health of Coles County’s farmers in mind, Eich said Rademaker visited the bureau in August 2019 to conduct a mental health first aid training course.

“(The training was) about how to deal with mental health, help that you can get for mental health and signs you can pick up on people,” Eich said.

Programming that helps farmers

Rademaker said rural hospitals like Carle Hospital are in the process of organizing different ways to train rural providers and rural communities to better understand mental health and how to help ag workers. Mental health first aid training is an example of one of these programs.

“Mental health first aid would be just like CPR or first aid,” Rademaker said. “It’s how do I help if I find someone in distress, what can I do until they get more advanced care or more help if needed?”

Rudolphi said much of the mental health first aid programming focuses on training people who or close to or interact with farmers instead of the farmers themselves.

“A really good example is what we did in Wisconsin was we trained people who support farmers, either professionally or personally, so we trained extension and veterinarians and firefighters and also spouses and siblings of farmers in mental health first aid,” Rudolphi said.

The first aid class Rademaker conducted at the Coles County Farm Bureau was an eight-hour course. She said her focus was on helping farm bureaus or other businesses or organizations that work directly with farmers on a day-to-day basis to better understand mental health and how they can help farmers.

The reason this type of training is geared toward people who work directly with farmers instead of the farmers themselves is the eight-hour aspect. Rademaker said farmers are just not going to be able to take that time out of their days to participate, so other methods need to be organized to directly target them.

There is also a national hotline that farmers can contact if they are contemplating suicide, suffering with mental illness or just want someone to speak with.

Rademaker said farmers are also strongly connected to their faiths, so she encourages farmers to reach out to their pastors, priests or clergies as well.

Rudolphi said another program is QPR, which stands for “Question, Persuade and Refer.” This is a suicide prevention training directed toward other non-mental health professionals.

These types of programs help bring communities together to help address mental health issues in agricultural fields, Rudolphi said. Having a sense of community for farmers is extremely helpful in getting them help, she said.

There are also some training programs meant specifically for farmers, Rudolphi said. They vary from lasting just 30 minutes to a day long, and they are somewhat scattered in terms of location. The can be either online or face-to-face.

Something reassuring Rademaker has noticed is that people are becoming more comfortable talking about mental illness within the agriculture field, she said.

“The main thing to it right now is people are willing to talk, and they’re seeing this happen with their friends and their neighbors and themselves, and so we’re trying to make sure that we’re there, that we’re getting the safety message out appropriately,” Rademaker said.

The 2019 Agricultural Disaster and relief for farmers

The United States Department of Agriculture declared an agricultural disaster on Aug. 8, 2019 in all Illinois counties because of flooding. The USDA has special programs that farmers will be able to take advantage of as a result.

According to the USDA, Sonny Perdue, U.S. secretary of agriculture, said he acknowledged the ongoing hardships farmers have faced since even before 2019.

“The scope of this year’s prevented planting alone is devastating, and although these disaster program benefits will not make producers whole, we hope the assistance will ease some of the financial strain farmers, ranchers and their families are experiencing. President Trump has the backs of our farmers, and we are working to support America’s great patriot farmers,” Perdue said.

However, Rademaker said the declared disaster and promised relief does not mean much right now because farmers and other agricultural workers do not yet know what that relief entails.

From Rademaker’s understanding, she said farmers will likely not know what sthe relief will mean for them until after harvesting is finished.

More thoughts on farmers and mental health

Rudolphi said something she has focused on in her research is how farmers prefer to receive their information on mental health.

One example she noted was how bankers have shown interest in mental health training for when they have to deny loans for farmers. They have expressed concerns about how they should communicate with farmers in those difficult financial situations.

“What we found out was that despite the bankers really wanting training, farmers didn’t want to hear a mental health message from their bankers,” Rudolphi said. “I think a better situation there is if a banker is going to deny a loan, then they make sure that their spouse or their children is aware of that, and (bankers) say, ‘Listen, so and so just left my office. He’s pretty upset; could you please reach out to them?’ because we know farmers want to hear, based on our survey, we know they want to hear and get that mental health message from their spouses, their close friends and their family.”

It all goes back to communicating with farmers about mental health being a community effort, which is what farmers respond positively to, Rudolphi said.

The agriculture community has been close for many years, but Rudolphi said she believes it is not always like that anymore. This is partially because of competitiveness in agriculture, but it might also be because fewer people are pursuing ag-related fields and farmers are living more private lives, Rudolphi said.

A great way to help would be for friends and family members to reach out to the ag workers they care about more often, she said. If people notice the farmers they interact with are struggling or facing hardships, sometimes just asking if they are OK makes a huge difference in their lives.

Additionally, Rademaker said farmers are becoming more comfortable sharing their struggles with others.

While farmers have sometimes been raised not to share those details about their lives, people across the nation are opening dialogues about mental health. That has had a positive effect on farmers as well, she said.

Rademaker and Rudolphi both said encouraging those same conversations to continue for farmers is paramount.

“I think every farmer needs to realize they are not alone,” Rudolphi said. “I know it’s hard to ask for help, and I know it’s hard to reach out or even to go online and try to find some resources, so that’s where I would call any of us who support a farmer personally or professionally, we be aware of what’s happening, and we be tuned into risk factors and warning signs and signs and symptoms so that we can ask the questions when our farmers aren’t able to ask for help.”

More on Rudolphi’s research

Rudolphi said her research, which is still in its early stages, focuses on finding more reliable ways of determining farmers’ suicide rates.

“My interests are in trying to identify if there are more reliable data sets to try to capture the instance of suicide among farmers, specifically in the Midwest, specifically in Illinois, because that’s where I am right now,” she said. “I focus a little bit more upstream, so I think we all understand that suicide represents obviously the most tragic, but relatively just the tip of the iceberg, in a big sea of suffering, and so trying to identify who is struggling with mental health disorders that may or may not be risk factors for suicide and who is struggling with chronic stress, which may or may not be risk factors for mental health disorders, so working a little bit more upstream to hopefully resolve some of the distress some people are suffering.”

After her research is complete, Rudolphi said she would hopefully distribute it to give Illinois a better idea of what should be done for farmer suicide prevention. From there, other prevention strategies can be discussed and organized to further assist farmers.

Logan Raschke can be reached at 581-2812 or at [email protected].