Coles County drug court: How the former ‘Meth Capital of Illinois’ responds to addiction

March 31, 2022

Every community strives to develop an identity that distinguishes it from the rest.

But none seek out the notoriety associated with Coles County in 2004: “Meth Capital of Illinois,” according to the Decatur Herald & Review.

Nearly 20 years later, this reputation still weighs heavily on the community.

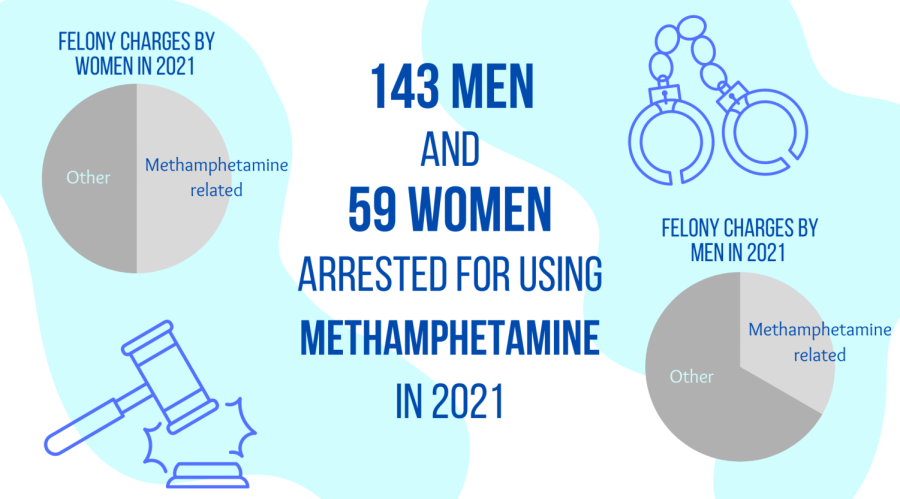

One-third of all 2021 felony charges by men in Coles County were attributed to methamphetamine, while the substance accounted for almost half of all felony charges by females.

That’s 143 men and 59 women who were arrested for taking the highly addictive stimulant that affects the central nervous system. More than 20,000 Americans died from meth overdoses in 2020, according to the National Health Institute.

Coles’ cultural and geographical factors predispose this rural community to methamphetamine abuse in comparison to urban or suburban areas. Similar factors also serve as roadblocks to achieving adequate levels of achievement in these same communities.

The 2004 article stated a combination of treatment, the legal system, and prevention would be needed to address the rise in methamphetamine in the county. Coles County responded with the creation of a drug court that same year.

Coles County developed a way to combat this community poison through a treatment-focused response to meth charges that is an outlier compared to other rural areas. Coles County drug court is an intensive probation program with rehabilitation at its core.

Despite the program’s sustained success, drug court still only has the capacity to accommodate 35 participants at a time.

Scope of the Methamphetamine Problem

Methamphetamine is predominantly seen in rural areas and use has been on the rise over the past decade. A drug chemistry laboratory in Ohio reported a nearly 80% increase in methamphetamine cases from 2010 compared to 2019.

Additionally, the 2017 Illinois Drug Assessment Survey classified Coles County in the highest of five categories regarding methamphetamine arrest rate.

Anthony Ortega said he was shocked at the amount of methamphetamine cases when he became the public defender for Coles County in 2013. Ortega had come from Champaign County, where he had encountered an estimated five to 10 methamphetamine cases in roughly nine years.

There are several components that led to methamphetamine’s prevalence in rural communities such as Coles County.

Methamphetamine used to be frequently manufactured in rural areas. Additionally, one of the main ingredients previously used to make methamphetamine, anhydrous, was easily accessible in farming communities.

Ortega recalled when he first started working in Coles County, many methamphetamine charges were related to manufacturing due to easy access to pseudoephedrine pills and other household items. However, these charges decreased after a law passed that required an ID to purchase the pills.

Ortega says methamphetamine in the area has since transitioned from homemade to “factory-made” methamphetamine that was introduced by Mexico. This methamphetamine is greater in quantity and potency, and Coles County still experiences easy accessibility due to its proximity to Interstate 57.

Although the types of methamphetamines have fluctuated over the years, one constant has been the drug’s prevalence in Coles County. Ortega said methamphetamine has been the driving force behind a lot of crime in the community throughout his eight years as the public defender, and data aligns with this sentiment.

In 2021, methamphetamine-related charges accounted for nearly one-third of all charges in felony cases for felony cases, and approximately 75 percent of methamphetamine charges were attributed to Coles County residents. Additionally, nearly 80% of all methamphetamine charges were classified as possession of less than five grams, which further illustrates the shift away from manufacturing charges.

Rural communities are generally not equipped to offer substantive substance use disorder treatment because of barriers in transportation and access to resources, according to Danessa Carter, an assistant professor at Eastern whose research focuses on addictions and counseling in rural areas. These communities typically lack an adequate number of treatment facilities or supportive services compared to urban areas.

Coles County Response: Drug Court

As a way to address the ongoing methamphetamine issue, Coles County has a drug court, which is a form of probation that centers on treatment and a high level of supervision. Successful completion of the program results in the drug conviction being removed from an individual’s record.

Carter noted the legal system can have a positive effect on those who suffer from substance abuse. She said individuals rarely wake up one day and admit they have an addiction; it often takes a major event, such as an arrest, to come to this conclusion.

However, Carter distinguished where the legal system goes wrong is with incarceration.

Carter admitted that prison is successful in keeping dangerous people off the streets, yet incarceration doesn’t stop people from continuing to be dangerous toward themselves or others.

Judge Brien O’Brien, the Coles County judge and drug court judge, said all drug users should not go to prison because research shows these individuals will repeat their crimes.

“The problem with that line of thinking is that it doesn’t change anything because, statistically, people who are addicts when they go to prison are still addicts when they get out of prison,” O’Brien said.

Carter said few prisons in Illinois offer substance abuse treatment, and these programs are underfunded and overwhelmed. Limited resources mean few inmates receive treatment.

O’Brien said an individual must be approved by the Department of Corrections in order to receive addiction counseling while in prison. Without a recommendation from a judge, there’s no chance the individual will receive counseling, but a recommendation does not guarantee treatment either.

Incarceration’s inability to address the methamphetamine issue led to the creation of the Coles County drug court in 2004, which O’Brien described as “an extremely intensive form of probation.” He said the court can be utilized by anyone with an addiction, but the court primarily sees methamphetamine users.

Drug court is designed to help those with drug convictions who have previously been in prison to receive treatment several times before – people who are in need of “a different solution,” according to O’Brien.

Those who find themselves in drug court often have exhausted all other options.

“If he’s gonna have a shot, this is it,” said Drug Court Officer Albert Adkins about a prospective candidate for drug court.

Drug Court Committee

Drug court features an eight-member committee whose primary duties are to determine who will be selected for drug court and to monitor them as they move through the program. The committee meets each Thursday at 12:30 p.m. in a closed meeting to discuss drug court members’ progress before drug court begins that same day at 1:30 p.m. at the courthouse.

Drug court committee has representatives from multiple arms of the legal system, as well as local counseling and mental health experts.

The committee consists of the following positions: judge (O’Brien), mental health representative (Christine Hughes and Tonya Franklin, LifeLinks Mental Health), treatment professional (Carter and Tammi Clancy, Hour House), drug court officer (Adkins), drug court coordinator (probation officer), prosecutor (Benjamin Hoover, assistant state’s attorney), public defender (Ortega) and law enforcement representative (Tyler Heleine, chief deputy Coles County sheriff’s department).

Selection Process

To be considered for drug court, an individual must have a pending charge, and their attorney must request a drug court evaluation to be approved by the judge.

The evaluation consists of an hour-and-a-half assessment conducted by Adkins, who interviews the candidate to determine their score on a list of objective criteria. The higher the score, the more at-risk they are considered, which improves their chances of being selected.

The drug court committee discusses the evaluation score, as well as other factors such as previous criminal history, education level, family situation or support system, housing, and transportation. The group must come to a consensus whether the candidate will be admitted; if there is no consensus, the final decision is left to the judge.

Not every person with a drug charge is eligible for drug court; certain circumstances deem an individual an inappropriate candidate who would not be selected.

Dealers are typically not accepted into drug court, although exceptions are made for individuals who sell drugs in order to fund their addiction. People with violent offenses, such as assault or battery charges are typically not selected for drug court out of an abundance of caution for the drug court officer who must conduct random home visits.

Additionally, there are certain charges that disqualify individuals automatically due to Illinois statutes. These charges include murder, predatory criminal sexual assault of a child and aggravated sexual assault.

Structure of Drug Court

The estimated time to complete drug court can vary from case to case, but the minimum amount of time to complete the program is two years and one month. To graduate from drug court, an individual must complete five phases.

Once an individual is selected for drug court, they go straight into residential treatment with Hour House in Charleston and they begin working on their phases. A minimum amount of time is attached to each phase, with the lowest being three months and highest being six months.

Each phase also has a varying level of supervision and restrictions; as one moves from phase one to five, these components lessen. For example, an individual in phase one must attend drug court every Thursday, while an individual in phase three must only attend every third week.

Below are the requirements that must be met in order for an individual to move from phase one to phase two:

•90 days in a row of sobriety

•Submit phase up request telling what was learned during the phase, what the individual intends to learn in phase two and how they’ll achieve this

•Abide by all the rules of the phase:

•Meet with drug court officer at least once a week

•Attend drug court at least once a week

•Attend a minimum of four community support groups a week

•Get a sponsor within 30 days of entering the program

•Attend all recommended counseling sessions

•Cooperate with all random drug tests

•Abide by 8 p.m. curfew

•No travel outside of the county unless for an emergency

•Complete community service if not employed

•Attend the monthly drug court support group meeting

•Work toward achieving stable housing and employment

Each phase has its own set of requirements, and the drug court committee has the final say on whether an individual will be phased up or not.

Throughout the program, individuals are expected to relapse or not follow the rules, so the committee is responsible for determining the correct sanctions. Ideally, the sanction is chosen to fit the severity of the infraction, or continued infractions. Examples of sanctions range from therapeutic adjustment and community service to small amounts of jail time and being phased down.

Success of Drug Court

O’Brien, Carter and Ortega have all had the opportunity to see the process of drug court up-close, and all sing nothing but its praises.

Carter says she “can’t stress enough” how impactful the drug court program has been in Coles County, boasting about the court’s accomplishments. Carter noted the court’s success lies in its outlook on addiction – rehab, not prison. She said the program recognizes addiction as a disease, so committee members often defer to Hour House’s treatment recommendations.

Ortega said he has seen the success of the program first-hand through the recent graduation of an individual whom he described as “out in the wild.”

“He never had a job, always intoxicated, just riding his bike around Mattoon using drugs, and now he’s a normal human being who works,” Ortega said.

Outside of personal testimony, reduced recidivism rates can also be used to measure the success of drug court.

Recidivism refers to an individual with a conviction for reoffending. Sixty-eight percent of drug offenders are rearrested within three years of their release from prison, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Substantial research illustrates that drug courts significantly reduce recidivism rates amongst drug offenders. Since O’Brien became the drug court judge in October 2016, there have been 48 graduates of the program. O’Brien estimates that no more than eight graduates have reoffended, which is approximately a 15% recidivism rate.

Possibility of Expansion?

The next step would be to expand and increase the current maximum capacity of 35 individuals.

According to Ortega, the drug court committee disqualifies cases with charges deemed Class Two, Class One, or Class X, which are the three most serious crime classifications.

Out of the 202 felony cases related to methamphetamine in Coles County in 2021, 51 cases had charges with one or more of these classifications. This means that there are 151 potential drug court cases.

Some of these cases feature repeat offenders, and not all of the individuals represented by these cases are guaranteed to fit the appropriate criteria to be selected for drug court; however, even if a quarter of these cases had individuals that would be a perfect fit for drug court, there would not be room to accommodate them.

Approximately 20 people are currently in the program, but the roughly two-year process means spots don’t become available frequently.

O’Brien would love to see the drug court expand to accommodate 50 people, or even twice that, one day. For this to be accomplished, more funds would have to be allocated for more judges, lawyers and, especially, drug court officers.

Adkins is the only drug court officer, conducting meetings and making random home visits each week for each drug court participant. O’Brien said he believes 15 to 20 participants is a manageable amount for Adkins, so even the court’s maximum capacity of 35 can be too many.

The question of acquiring the funds needed for drug court expansion would be one for the Coles County Board, said Ortega.

Barriers to Expansion

The county currently does not allocate enough funds in order to finance the addition of the necessary positions for expansion.

But that’s not the only challenge.

There’s also the stigma surrounding addiction that serves as a roadblock to a communities’ ability to prioritize rehabilitation as the preferred method of addressing drug charges.

Carter said this stigma is more difficult to break in rural communities. This is because these communities generally have a “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” mentality and individuals are often taught to keep problems to themselves.

“There’s much more resistance to accepting the disease model of addiction that it is a brain disease,” Carter said. “It’s a chronic and pervasive relapsing disease, but instead it’s looked at like a moral failure or inability to choose right from wrong.”

Carter emphasized that rural communities often have government institutions that view substance use disorder as a moral issue, rather than a health issue.

The answers for breaking the stigma lie within the community.

Carter said a key to breaking the stigma is to reduce the anonymity associated with addiction.

Reducing anonymity is as simple as listening to community members’ recovery stories to hear about their productive and healthy lives. Carter said this is “a really powerful thing,” especially when someone is learning from a person they know or look up to.

O’Brien said he encourages community members to attend drug court on Thursdays. He said it would be a prime opportunity to see first-hand how the program operates, as well as the progress being made by fellow community members.

Education is also essential, Carter said. It is imperative that the perspective shifts from seeing addiction as a moral failure as opposed to the brain disease it actually is.

O’Brien said he tries to do his part to educate the community on drug court by speaking to clubs in the area whenever he is invited. He admitted that he had his own misconceptions about drug court before becoming the judge over five years ago.

“When I became the drug court judge, I was pessimistic,” O’Brien said. “I was in the school of thought that if you break the law then you should be punished, and you need to go to prison. But then I was enlightened.”

O’Brien attributed his shift in mindset to the mandatory training that each person must complete before serving on the drug court committee.

Addressing Relapse

Addiction is a constant battle and recovery is a lifelong process, said Carter. While graduation from drug court reduces the chances of relapse and reoffending, these outcomes are definitely a possibility. Relapse throughout the process of drug court, especially in the first phases, is almost expected.

If relapse is expected, the question then becomes how many chances should an individual be afforded?

Jesse Danley, the state’s attorney for Coles County, believes there are two schools of thought when answering that question, with no middle ground between the two.

Danley said one camp of thinking centers on rehabilitation. Individuals that subscribe to this thinking advocate for multiple chances until the treatment sticks.

Danley described the second viewpoint as “the prosecutorial-minded people,” which he identified with. He said he supports drug court, but says that if people on the court don’t take advantage of their first couple of chances, then it is time to “move on.”

He attributed this mindset primarily to his department’s limited resources, stating that he didn’t want to “waste tax dollars” on prosecuting the individuals who continually reoffend.

“I’ve got a judge right now on the felony bench that believes addicts deserve as many chances as it takes, and I am tired of filing these drug offense charges on the same person,” Danley said.

Danley admitted this way of thinking is “cold and calculated,” but he deems it necessary for his department to operate effectively with the resources allotted.

Danley, a drug court proponent, acknowledged that prison will not fix the root cause of methamphetamine crime, saying it should be used when it’s “the only tool left in the belt.”

Carter said the response to a person’s continually reoffending should be to “keep assessing.” She said sometimes there’s just one aspect missing to reaching that individual’s successful treatment strategy. Her outlook was largely influenced by her father, who also worked in addiction counseling.

“My dad has this saying that as long as somebody’s still breathing, there’s still a chance for recovery,” Carter said. “It’s only if they’ve died that we’ve lost any of that opportunity.”

Carter added that there is no rhyme or reason to recovery; one never knows when everything will click for them.

“So I think we keep trying. And, no matter what, we have to remember to be grateful for every day that there is recovery,” Carter said.

Lauren Frick can be reached at 581-2812 or at [email protected].